It’s been a long week. When I first started out with this blog, I hadn’t quite yet anticipated what I would be writing about regularly. My goals were to explore my identities as a Christian, an Asian American, and a writer. #GeorgeFloyd and surrounding events, news, and personal conversations have given me a lot to think through and process. As a writer, I write to understand my own thoughts. I also write to share and invite discussion. As a Christian, I care deeply about the sanctity of each and every human life born in God’s image. The Christian identity is both steadfast hope in Jesus Christ’s redemption AND active participation emulating and extending his love to the whole world—that is why I care deeply about justice. And finally, I believe Asian Americans have a unique role to play in this seemingly “black-white” racial divide that has permeated all of American history. We have our own story, our own tensions, our own complicated messes… but we are here.

I recently stumbled upon David Kantor’s “Four Player Model,” a model that illustrates the four different roles that people take on in a conversation (I love observing social behavior and group dynamics, so I found this fascinating). I think it also gives particular insight into the discussions and reactions I see in response to #GeorgeFloyd. The four roles are:

-

Initiators—propose a new idea, initiate, carry the focus of a conversation, assert a claim

-

Followers—support what is being said, expand or add, agree or symbolically aligns with the initiator

-

Opposing—challenges, corrects, “stands” in-between the initiator and follower, gives alternative views

-

Bystanding—observes, stays outside the immediate conversation, gives perspective, reflects to the group

The easiest explanation is by running through an example, so take this imaginary conversation between a group of friends and observe the different roles that each statement is associated with:

-

“Let’s go get boba for dessert!” (initiator)

-

“Totally down – Teaspoon?” (follower)

-

“Teaspoon is way too far to drive… let’s do ice cream instead.” (opposer)

-

[After being prompted:] “Well… it is Person 3’s car… how about Sharetea, or are people down for Salt & Straw?” (bystander)

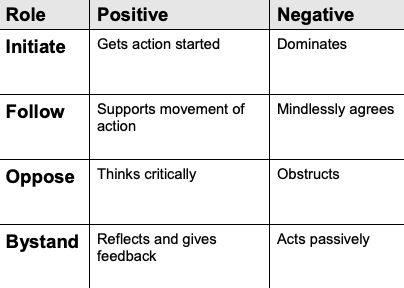

So to be clear, the point of David Kantor’s model is that ALL four roles are necessary in a conversation. No role is inherently “better” than the other. In fact, each of the roles have positive and negative characteristics associated with them, and a person can shift and play multiple roles in any given conversation:

Each role has negative and positive traits

Each role has negative and positive traitsBut the question to my Asian American brothers and sisters (or to any reader): in the current racial injustice climate, which role do you find yourself playing the most? What strengths do you bring to the table? Which role(s) in this model above could you grow in?

But the question to my Asian American brothers and sisters (or to any reader): in the current racial injustice climate, which role do you find yourself playing the most? What strengths do you bring to the table? Which role(s) in this model above could you grow in?

I’ll speak for myself that I feel most comfortable observing, thinking, and then vocalizing my thoughts only when someone invites me into a conversation—I’m most naturally a bystander. Looking at the right side of the chart above, I clearly don’t mindlessly agree to things. But I also tend not to obstruct other people’s point of view. I might disagree quietly, but I wait until I’m prompted before verbalizing it out loud. And therein might be the problem.

Different situations call for different responses. Sometimes, being a bystander is a real asset and strength. In a confrontation between two friends, for example, you might be able to give helpful perspective, mediate conflict or mutual understanding, or at the very least help each party feel heard because you haven’t jumped into the argument and thus remain “neutral.” In other situations though—when a human being is slowly suffocating to death because another human being is kneeling on their throat—remaining a bystander has deadly and moral consequences. And that’s not just a one-off condemnation of Hmong-American officer Tou Thao. He was one individual in one specific scenario. That scene—an Asian American officer in power looking aside as a white officer in power cruelly and methodically squeezes the life out of an unarmed black man on the ground—is incredibly symbolic of a much larger symptom. A symptom of which I am not separate from.

I confess that in the larger Black Lives Matter movement, I personally have been passive as a default. I hide being the excuses of “the issue is too big for me to have any real impact” or “there doesn’t seem to be a way to engage productively.” But in some ways, I’ve realized this past week has given me opportunity to simply pause and reflect. And determine where I can make small, incremental change. Reflecting and sharing insight by way of blogging is one way of leaning into the positives attributes of being a bystander. But orienting myself in the chart above also makes me wonder if it’s time to step into different and perhaps more uncomfortable roles in the conversations I am a part of. Where can I be an opposer? In what situations should I be a follower? And when should I be an initiator?

Broadly speaking, historically speaking, allegorically speaking… Asian American voices in America have largely been silent on matters of race, injustice, and anti-blackness. But broadly speaking, allegorically speaking, and perhaps personally speaking… part of that is because Asian Americans don’t believe their voices are important enough to be shared, just as they are. If you’re at all interested in exploring with me what that voice could be or even should be—leave me a comment below, follow this blog for future posts, or direct message me! As I alluded to in my last post, I would love to start simply by listening to your thoughts.

Question: which role (initiator, follower, opposer, bystander) do you most identify with and why?

Be First to Comment