I’ll admit it. I always hated history growing up. It was my least favorite subject—memorizing dates and disjointed facts just never seemed that relevant nor important to me. It wasn’t until my adult life, until very recently, that I’ve been motivated to try and understand my parents’ history more fully, to hear their stories and interpret their narratives in order to better comprehend my own. I have come to realize that identity and history must go hand-in-hand. As a second-generation Chinese American, the Chinese part of my identity requires that I recognize and honor my family origin. At the same time, the American part of my identity stipulates that I take the time to understand the history and policies that have shaped the very society that I live in.

The first time I heard about the model minority myth, I wasn’t sure which part was the “myth” part. I grew up embodying the term “model minority”—academic vernacular for “smart asian”—because I performed well in school, rarely got in trouble, and participated in lots of extracurriculars. But I wrongly assumed that the “myth” stopped there; I thought dismantling the model minority myth was simply rejecting those stereotypes of “math whiz” or “asian genius.” It wasn’t until later that I realized the danger of having such a narrow and self-focused lens—funneling a systemic reality into an individual perception only produces a half-baked “truth” that, in light of a wider American history, proves far more sinister than not acknowledging it at all.

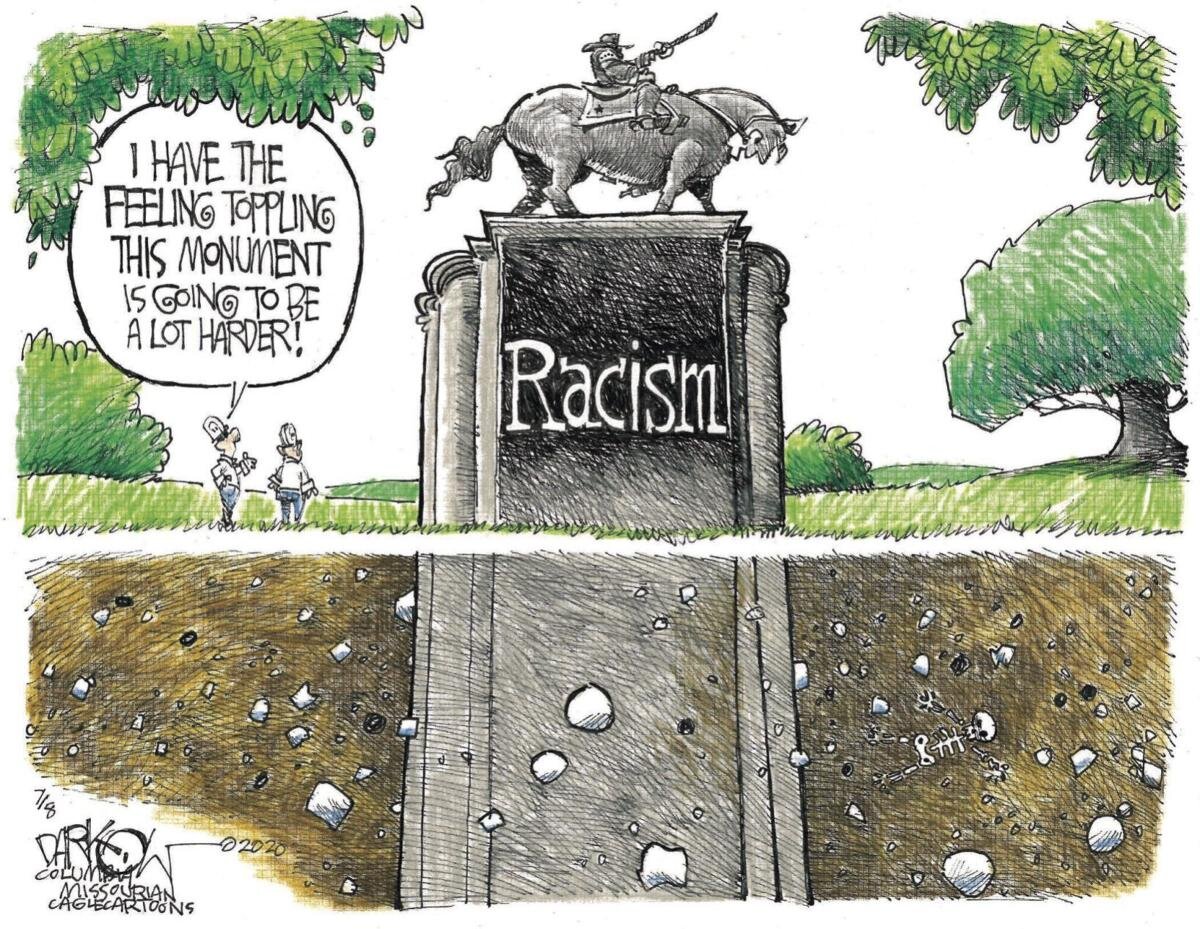

As I’m understanding the model minority myth, the issue isn’t that Asian Americans are put on a pedestal, or stereotyped as smart, successful overachievers. The issue is that that particular pedestal of “successful East Asian immigrant” rests squarely on the backs of Black Americans and other racial minorities in America, crushing and denigrating them for their lack of achievement and social mobility. It lets the rest of a racist society off the hook by having a scapegoat population to point to in order to invalidate the existence of a racial inequality for others. The Hart-Celler Act, also known as the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, replaced the national origin quota system in favor of a preferential system: one that first gave preference to family reunification, then secondarily to highly-educated workers. It is hardly fair to compare these skilled immigrants—your engineers, doctors, teachers—to blacks in America still trying to throw off the stubborn shackles of Jim Crow laws, economic redlining, and mass incarceration and criminalization.

History is not a compilation of saran-wrapped individuals who have no impact on each other whatsoever as they move through time and space. Truly recognizing and dismantling the model minority means more than shedding a stereotype—it means seeing the entirety of the Asian and Pacific Islander experience and acknowledging other narratives—Filipino, Cambodian, Vietnamese, among others—as different from my own. It means empathizing with native and brown populations that are erased or forced aside as a result of a racial hierarchy that wedges East Asians in between whites and other minorities. It means acknowledging and bringing to light the Black narrative and anti-blackness systems that have pervaded our nation since preconception.

To me, understanding the history behind the model minority myth and its repercussions on my own identity helps me respond more aptly to Black Lives Matter, a movement that strives to give voice to the pain and unjust sufferings of the black identity in America. Learning where the model minority myth intersects with my family narrative and the narrative of those around me actually enables me as an Asian American to more easily grapple with and recognize the subversive nature of structural racism in our country: a pervading force that is systemic and subtle but never “intentionally” prejudiced. We are all on this boat called systemic racism—an unconscious but embedded hierarchy of putting whites on top and blacks on bottom. The sooner we can recognize that we are on this boat together, collectively trapped in this system of oppressor and oppressed, the sooner we can cry out to our Lord Savior and collectively repent.

The model minority myth has forced me to consider race and racial experiences from a collective, rather than individualistic, stance. The first and foremost step in responding to a cry to fix a sinking ship is to start with the recognition that it is indeed a collective ship. Not a flotilla of little sailboats, not a line of individual kayaks… no, a ship. Ships have motors and a steering system that were designed to keep it propelling in a certain direction. They have purposeful design and principles by which they were fashioned into being. They have incredible momentum and inertia. Unless you are actively trying to turn the steering wheel, wake others up to sound the alarm, or heck—take up an individual wooden oar (as futile as paddling may seem, do not forget that war galleys up until the early modern era were powered by exactly that…), you are doing nobody any good by standing by with inaction or complacency. The Black Lives Matter movement is such a cry—we are in a sinking ship, and black lives are drowning. You can see how complicity, apathy, or denial from people on the top deck of the ship would be received with feelings of frustration, anger, and betrayal.

The model minority myth allows me to recognize we occupy different rungs in society’s racialized structures, often not by choice. I speak and write English fluently and therefore can tap into a power and position that my parents as immigrants never had. Similarly, my parents as East Asian immigrants had access to a privilege and perception of “law-abiding citizen” and “hardworking immigrant” that black people simply are not afforded in this country. As a broad and diverse community, Asian Americans have an expansive vantage point with which to see systemic racism in America. We have members strewn along the full spectrum. Some of us have been conditioned to the idea that there is nothing wrong with enjoying the top deck on a relaxing cruise that you worked so hard to pay for. Some of us are down there drowning with everybody else, or preoccupied just barely keeping our own necks above the water line. Still others of us might feel like we’re in the crow’s nest—able to see and observe what is happening clearly, but powerless and voiceless to change anything that is happening.

The model minority myth makes it clear to me that identity and history are inextricably tied. As a Chinese-looking male, I’m able to acclimate and navigate society in a particular way due to my parents’ backgrounds, the way Chinese immigrants have been regarded by others historically, and the opportunities I had access to growing up. I may not be the reason why the model minority myth exists, nor is there an explicit, intentional culprit behind it all that I could point toward; yet, the reality and implications of it still very much exist, and the history of that racialization affects and impacts my life. The reason why blacks have it so hard in America is because from square one, before any other determining factor, they inherit the legacy of hundreds of years of slavery, discrimination, and embedded black inferiority. History shapes identity and it shapes narrative. When people talk individualistically and deny being “racist,” they are trying to cut the tie between history and identity. This is where being Asian American—and having a collectivist awareness that I am the product of all who came before me—makes me incredibly empathetic to the need for a movement that, in the wake of an unjust history, calls for necessary recognition and change for black lives in America.

I have come to see that I need to take responsibility for my own individual life and actions, yes. But I also must contend with a portion of my identity that has been dealt to me—drawn from the history of my family, the history of the country I live in, the history that extends past my individual self to all the people sharing in my racial identity before me. The model minority myth has shown me that I was given a script and an identity to play in this country even before I had conscious awareness of it. It has pulled me deeper into an investigation and examination of the laws and structures that are rooted in this country’s history. And it’s helping me to see that systemic racism is real, it is covert, and it needs active attention in order to change. Black lives historically have not mattered in this country—that is no myth. What matters is how the rest of us, Asian Americans fully included, choose how to respond.

Be First to Comment